Your body’s need for energy varies widely throughout a 24-hour day. When you’re asleep, it is relatively low. When you wake up in the morning, you need an energy boost to support increased heart rate, muscle motion, and brain activity, as well as other functions. When you engage in exercise and sports, energy is needed to meet the increased demand of your muscles.

This is all routine, business as usual. What may not be routine, however, is the occasional need to protect yourself from attack. In prehistoric times, those attacks might come from an animal, from other humans, or from the weather. In civilized times, the threat is more likely to be a high-stakes job interview, or figuring out how to pay the bills, or a traffic jam.

Whatever the threat, human bodies have evolved to make sure there is plenty of energy available for the brain and muscles, allowing for quick thinking and reaction time whether you choose fight or flight. So when a threat is perceived, glucose production is accelerated and fat is broken down more rapidly into fatty acids.

Once the danger has passed, and that extra fuel has been expended in outrunning or outfighting the danger, body systems return to business as usual.

At least that’s the way it’s worked in prehistoric times. To understand what happens in modern times, we need to look more closely into the machinery.

First, realize your liver, heart, and fat cells have no way of knowing directly that there’s danger in your environment—that’s information that’s collected by your senses and transmitted to your brain along nerves. You interpret that information as danger, and a switch flips in your brain—actually, it’s probably thousands of switches–that starts the ball rolling.

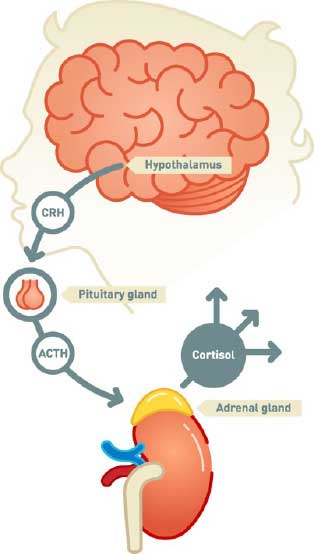

There’s a part of your brain whose primary job is to interface between the rest of your brain and your body in circumstances like these. It’s called the hypothalamus.

When those switches flip in your brain, the hypothalamus releases a hormone whose name isn’t important. That hormone travels through your bloodstream to a gland in your body called the pituitary gland, which is then triggered to release another hormone whose name isn’t important. And THAT hormone travels to your adrenal glands (which sit on top of your kidneys), causing them to release a hormone whose name you DO need to know, because that’s the hormone that your body responds to in order to make sure there’s plenty of fuel available. The name of that hormone is cortisol. It’s also sometimes called hydrocortisone.

Cortisol is powerful. It stimulates the liver to convert glycogen to glucose. It stimulates fat cells to break down fat into fatty acids. It can even stimulate the breakdown of proteins in your muscles into amino acids and cause those amino acids to be converted to glucose.

And so your body is flooded with fuel, plenty of energy for your brain and muscles to respond to the threat.

That’s all very good news if you’re outrunning an angry mastodon. But what if you aren’t? What if the threat your brain perceives is trying to get to work on time for a critical meeting in a traffic jam?

Instead of outrunning a mastodon, you’re sitting in traffic. Now the extra glucose and fatty acids in your blood aren’t required by your muscles. To put your body back into balance, those fuels need to be converted back into the storage form from which they came—that is, glycogen and fat.

You might be thinking, “OK, so everything goes back to the way it was, no problem!” It would be nice if it worked out that way, but for reasons not wholly understood, it doesn’t. What actually happens is that in the process, extra fat is deposited around your organs, in your belly region. That’s called visceral fat, and higher levels of visceral fat are known to raise the risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Does this mean that being stalled in traffic increases your risk of a heart attack? Certainly not if it happens once, or for a short time. But chronic stress, stress that you experience continually or repeatedly over a long period of time, IS unhealthy for precisely this reason—it can lead to an accumulation of visceral fat and increased risk of diabetes and heart disease.

So when you’re late for work, stressed and flooded with fuel, the healthiest thing you could do is to get out and walk briskly to work—burning up the extra fuel and at the same time realizing the other benefits of exercise.

But the healthiest choice is not always a practical solution. For that, watch for the upcoming new eSavvyHealth course on Energy Management, and in the meantime make getting a good night’s sleep and daily exercise/physical activity a priority. (And it’s worth noting that some studies have found Tai Chi to be an effective method of lowering cortisol.)

Changes in heart rate, noradrenaline, cortisol and mood during Tai Chi